Perhaps the phoebe selected her nesting spot during the few days my family was away from home at the end of April. Otherwise, I can’t quite figure her decision to build a nest atop the back porch light, right next to a doorway used regularly by three children and a rambunctious puppy.

To protect the nest, we took to unloading the minivan on the other side of the house, avoiding the back door altogether, and moving into and out of the adjacent garage as quietly as possible. No doubt, we’re not alone in changing our habits for the sake of a resident phoebe family.

“It is very typical of phoebes to nest on houses. They don’t seem to be super bothered by foot traffic,” said Robyn Bailey, project leader for the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Nest Watch, who noted that beyond porches, phoebes often nest under eaves, in garages, on bridges, and even in culverts. “Historically they would have nested in a cave or rocky outcrop, and we’ve kind of created these artificial caves for them.”

As with most small songbird species, the female phoebe is the primary builder. From the kitchen window, we were able to watch the nest quite literally take shape. The mud was the first thing we noticed, a dark mass of it atop the light and affixed to the side of the house, with a few wayward splatters against the wall and the ceiling.

“Phoebes carry the mud in their beaks and can apply the mud directly to the surface they’re perching on. They’re also capable of building an adherent nest, which sticks to the side of a building,” said Bailey. “In that case, they hover and kind of throw the mud [onto the surface].”

It can take up to two weeks to complete a phoebe nest. Our bird certainly seemed to take her time. Days after the mud had dried, she started making trips to the foundation with a beak full of moss, the second type of material found in most phoebe nests. The final touches were made with dried grass and bits of animal fur (possibly from the aforementioned puppy) packed inside as a lining.

For a few days after the nest was complete, I didn’t see the phoebe at all, despite my regular anxious glances out the kitchen window. This is not surprising; it’s typical for a week or two to elapse between nest building and egg laying. Then one morning, I noticed that she was back, briefly, on the nest. When she flew away, a peek into the nest revealed two eggs. She added an egg every day after that until there were five small, cream-colored eggs.

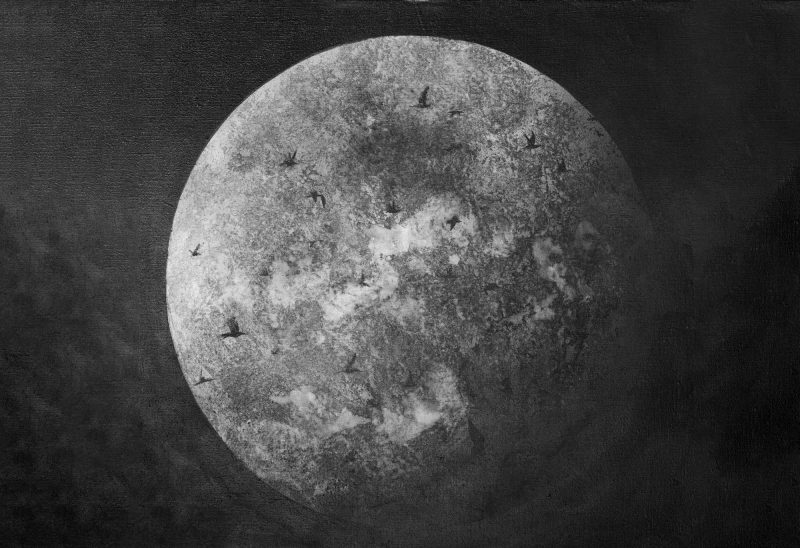

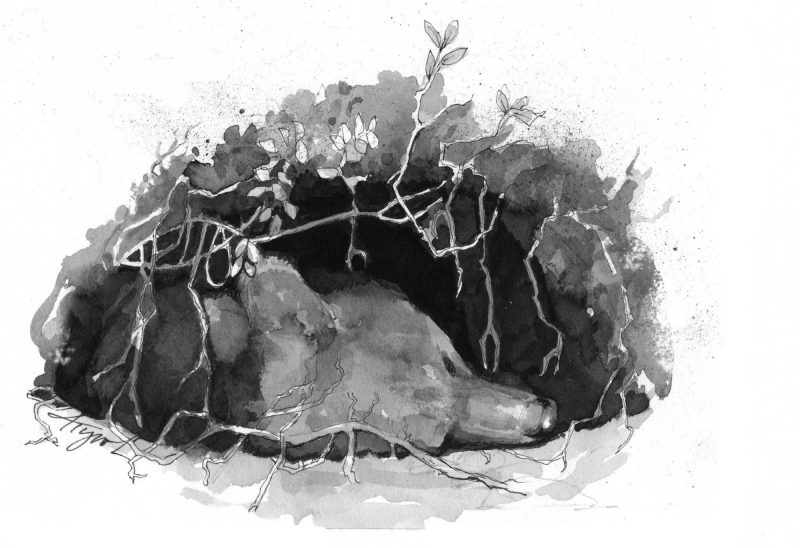

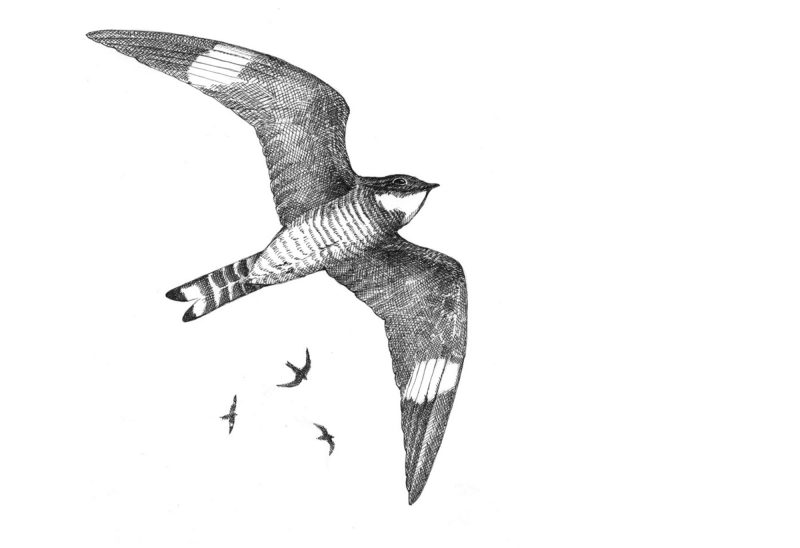

Phoebes. Illustration by Adelaide Tyrol.

Once her clutch was complete, she was often – but not always – sitting on the nest. Sometimes just her gray-brown head appeared above the rim. Other times her notched tail stuck out from one side as she kept a lookout on the driveway, house, and humans. I often hear the namesake, raspy “Phoe-be” call from nearby, probably her mate, announcing his territory.

At first I worried about the occasional but sometimes lengthy absences from the nest. But Bailey explained that phoebes exhibit lower nest attendance than many other birds, spending as little as 57 percent of the 15- to 16-day incubation period on the nest. When our phoebe was absent, she was likely out catching the flying insects and other invertebrates that make up her diet.

Then came the day that I discovered the mother phoebe perched on the edge of the nest, rather than sitting within it. The eggs had hatched, and the nest now contained mostly-naked chicks. They grew quickly, and we caught glimpses of gaping beaks each time a parent arrived bearing food.

Ten days after hatching, the chicks, now feathered, opened their eyes. The nest was becoming crowded. At two weeks of age, the chicks seemed increasingly restless, flapping their wings and shaking their heads (although that could be because of the parasitic mites, which crawled in black-dotted masses all around the nest). They began perching precariously on the edges of the nest.

One afternoon, a week into the kids’ summer vacation from school, we returned from an outing and found an empty nest. The chicks had fledged.

Phoebes often have two broods each year, and once the first chicks are on their own, the mother begins the nesting process all over again. Frequently, that means refurbishing an old nest – or one vacated by other birds – building the edges a bit higher and adding new lining material to the interior to freshen things up for each clutch of eggs.

Because the mites are so prolific at the old nest, I’ll likely remove it and wipe the porch down to eliminate both mites and the bird droppings that have accumulated over the past few weeks. But I hope the phoebes come back to rebuild. We’ve become accustomed to tiptoeing past the back door, and the porch seems a lonely place now without our bird family.

This Outside Story feature was written by Meghan McCarthy McPhaul, an author and freelance writer in Franconia, New Hampshire. The illustration was drawn by Adelaide Tyrol. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine, and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation, a fund dedicated to increasing environmental and ecological science knowledge: jryyobea@aups.bet. A book compilation of Outside Story articles is available at http://www.northernwoodlands.org.