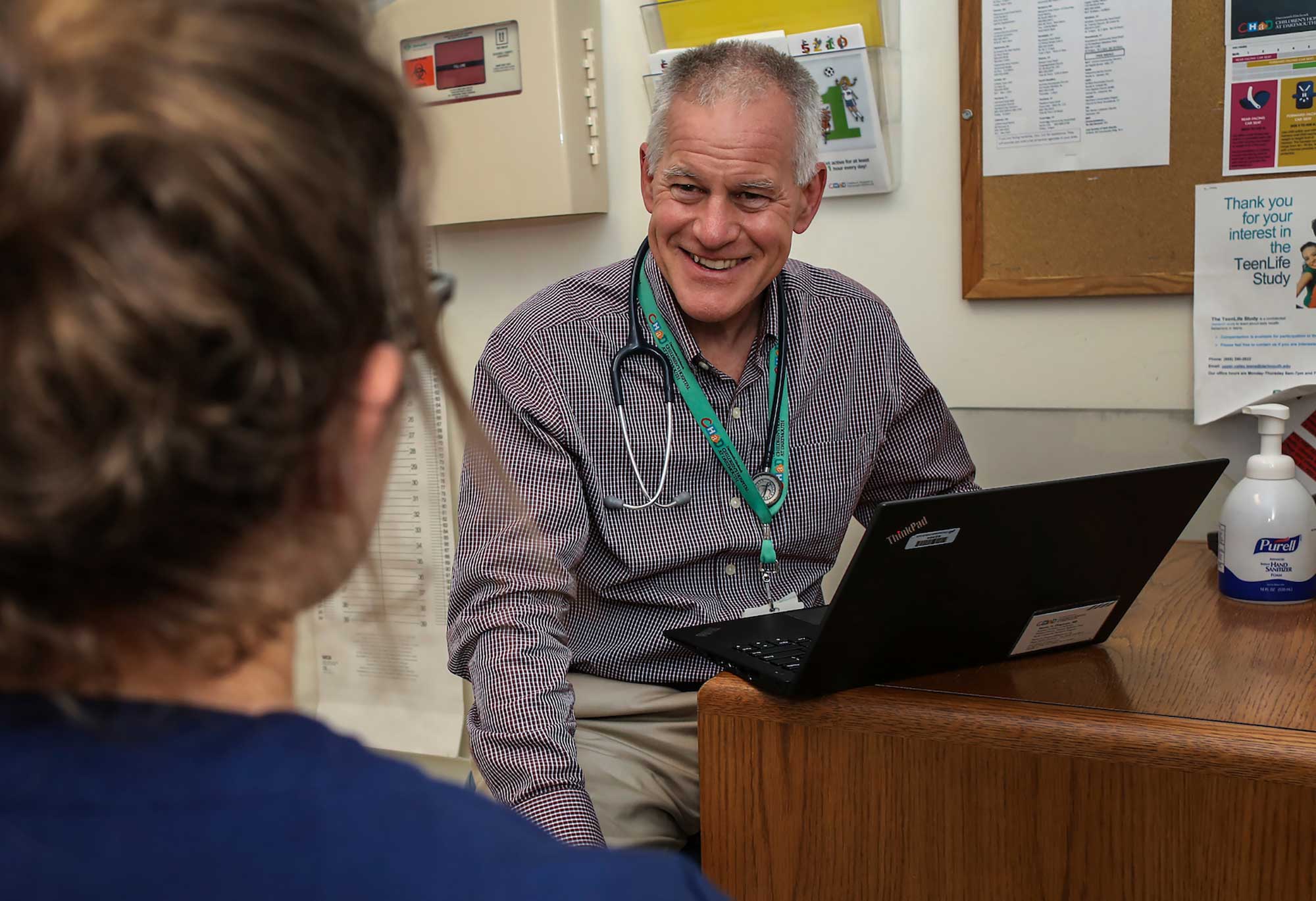

For Dr. Steve Chapman, SBIRT provides the chance to seize an opportunity that used to go right by.

“We did a good job at immunizations and screening your vision and hearing and other things,” he said, “but one of the most important health issues, substance misuse, we were not routinely addressing.”

Now, Dartmouth-Hitchcock has implemented SBIRT in well-child visits at six pediatrics practices for patients 13 and older.

“When asked, kids answer,” Chapman said. “And we ask regularly, and say ‘my job is to help you be as healthy as you can possibly be.’” When a young person is not using drugs and alcohol, Chapman has the chance to say “That’s great. I’m really proud of you for making good choices. Most kids your age are making those same choices.”

SBIRT, he said, “has created the expectation that we will talk about it and we will pick up where we left off” at each subsequent visit. The consistency builds trust, and establishes the conversation in a medical setting.

The use of SBIRT, Chapman said, “has opened all sorts of doors. I had someone who had a negative screen and then, three months later, his mom called and said ‘he got caught drinking and got suspended from school and he wants to come and talk to you.’ And that’s because I screened and said ‘let’s talk about it again.’” Chapman talked through the incident with him, and referred him for the counseling he needed to get back on track.

Dartmouth assembled a multi-disciplinary team to get SBIRT up and running, including teens and parents who helped write questions used in the screening.

Initially, Chapman said, some providers were hesitant to add SBIRT to their routines. “Providers have groups coming at them all the time to do one more thing, whether it’s oral health or concussions or how much you’re on your cell phone or substance misuse…getting past that to where it’s recognized as one of the top unaddressed issues in health care, including in pediatrics, is a challenge.”

He said that providers now understand that “this is a problem that begins in adolescence and we have an opportunity to engage and there are ways to do it that don’t take more time that don’t annoy patients and are really rewarding.”

“Kids want to be helped, parents want their kids to be helped, and we want to help. Once you start” using SBIRT, he said, “it’s pretty clear that you’re in really powerful territory.”

SBIRT used in obstetrics practice

Grant funding helped purchase electronic tablets for obstetric patients in Dartmouth-Hitchcock’s women’s health practices to use in completing the SBIRT questionnaire. That allowed the protocol to be more seamlessly integrated into Dartmouth’s systems.

SBIRT “has caused us to think more deeply about the role that drugs and alcohol play in women’s lives,” not only during pregnancy but before and after, said Daisy Goodman, a certified nurse midwife who leads Dartmouth’s obstetrics and gynecology practices. “It has enriched our role as OB providers in helping women to be great parents.”

She said it is critical, when using the protocol, to have a current list of treatment resources available and a dedicated staff person with the time to maintain information and relationships for those referrals.

“It is up to us to advocate, to be sure we have pathways to treatment,” Goodman said. “It’s a responsibility we take on: to see the patient through to the next step if treatment is indicated.”

Using the protocol, she said, has helped break down stigmas about substance use disorders, which helps expectant moms can get the care they need and improves outcomes for mothers and babies.

“It’s crucial for us to think of substance use disorders like any other chronic medical condition that we screen for,” Goodman said, “The problem is that substance use disorders have been described as a moral failing or some kind of behavioral pathology rather than as a disease process – which they are. If we really understand substance use disorders as a chronic disease process, we convey that to our patients and have a medically-based, scientific conversation about what they need. We need to take it out of the moral realm and have it live where it belongs: in the medical realm.”

![Rev. Heidi Carrington Heath joined Seacoast Outright. [Photo by Cheryl Senter]](https://www.nhcf.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Heidi-Carrington-Thumbnail-800x548.jpg)

![Dr. Jennie Hennigar treats a patient at the Tamworth Dental Center [Photo by Cheryl Senter]](https://www.nhcf.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/TCCAP-Hero-800x548.jpg)