This post was updated on March 25, 2021.

ZIP code should not determine educational opportunity or outcomes.

But in New Hampshire, all too frequently, it does.

The American Institutes for Research analyzed ten years’ of New Hampshire data and last year produced a report for the state’s Commission to Study School Funding. Among the findings: In New Hampshire, “The highest poverty school districts have the lowest student outcomes. The negative relationship between poverty and outcomes is very strong.”

Gaps in opportunity and outcomes are perennial and persistent. The COVID-19 pandemic has widened those gaps — hitting already struggling families and school districts the hardest.

These discrepancies translate into real consequences for children in struggling school districts: Much lower teacher salaries and higher teacher turnover; lack of access to art, music, or AP classes; outdated textbooks; few or no behavioral health and counseling supports for young people in crisis; obsolete technology; even school closures in some communities.

There are no easy answers to this complex set of challenges. But never has it been more urgent to try to solve this.

In partnership with generous donors, the Foundation is supporting two nonprofit organizations that are addressing these issues in tandem: Reaching Higher New Hampshire, which provides content and analysis on policy and legislation affecting public education, and the New Hampshire School Funding Fairness project, which advocates for a more equitable system to fund public education to ensure that all children have equal educational opportunities and taxpayers share the cost of that education more equitably.

The Foundation is not advocating for a particular solution to this crisis at this time. But we do have to face the fact that this is a crisis, and work together toward a solution so that all of New Hampshire’s children — no matter where they live or how much money their parents make — can rely on their local public school to give them the educational foundation in life that they deserve. These investments are part of the Foundation’s overall commitment to equity and part of its New Hampshire Tomorrow initiative to improve outcomes for children and families who face barriers to opportunity. Over ten years, the Foundation is committing a minimum of $100 million in four focus areas: early childhood education, family and youth supports, substance use disorder prevention, treatment and recovery and education and career initiatives.

All students in New Hampshire should have equal access to educational opportunity so they can thrive in school, graduate and grow into adults who are able to help sustain New Hampshire’s communities and economy. Reaching Higher New Hampshire and the School Funding Fairness Project are doing incredible work on behalf of New Hampshire’s children.

Reaching Higher New Hampshire

Reaching Higher is nationally known for its work supporting education innovation and family and community engagement to improve learning. In 2019, its bipartisan board named New Hampshire school funding as the organization’s top priority, with a focus on research and analysis, community engagement, and communications. Foundation support has allowed Reaching Higher to add an experienced project manager and a part-time journalist/storyteller to bolster its capacity to address school funding issues. Reaching Higher has provided high-quality data and analysis to inform the New Hampshire Commission to Study School Funding, the Carsey School for Public Policy, the American Institutes for Research, New Hampshire School Funding Fairness Project, and the public. Its recently released Whole Picture of Public Education in New Hampshire, offers comprehensive research into New Hampshire student learning and outcomes, and the organization expertly led a community engagement process to champion student success for Manchester Proud.

NH School Funding Fairness Project

The New Hampshire School Funding Fairness Project, founded by community leaders from around the state, led by Doug Hall (former state representative and director of the New Hampshire Center for Public Policy Studies) and John Tobin (former director of New Hampshire Legal Assistance) works to raise public awareness and seek legislative solutions to New Hampshire’s funding inequities. The organization successfully advocated in the New Hampshire legislature for creation of the Commission to Study School Funding, and helped secure a budget that provides an additional $130 million in aid for local schools, much of which is directed to communities in greatest need of that aid.

Foundation support allowed the School Funding Fairness Project to hire its first staff member, Jeff McLynch, former executive director of the New Hampshire Fiscal Policy Institute, to advance advocacy and policy work.

Inequities are apparent, and stark

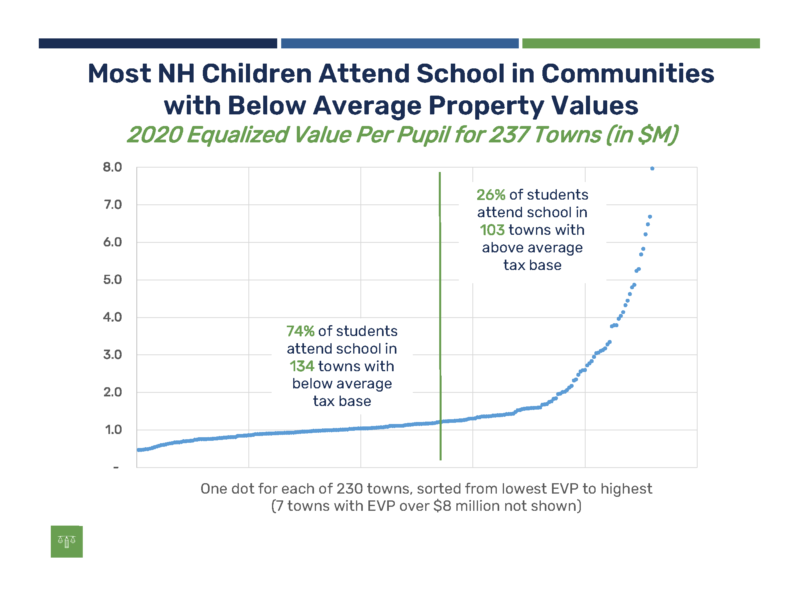

New Hampshire’s state constitution mandates that the state provide an “adequate” education to all children. Since a coalition of “property-poor” towns sued the state in the 1990s, various funding formulas have been applied by the legislature — all of which have continued to rely predominantly on local property taxes to foot the majority of the bill for public education. The amount the state sends to districts remains far below what districts must spend. And nearly three-quarters of students in New Hampshire attend school in communities with below-average property values.

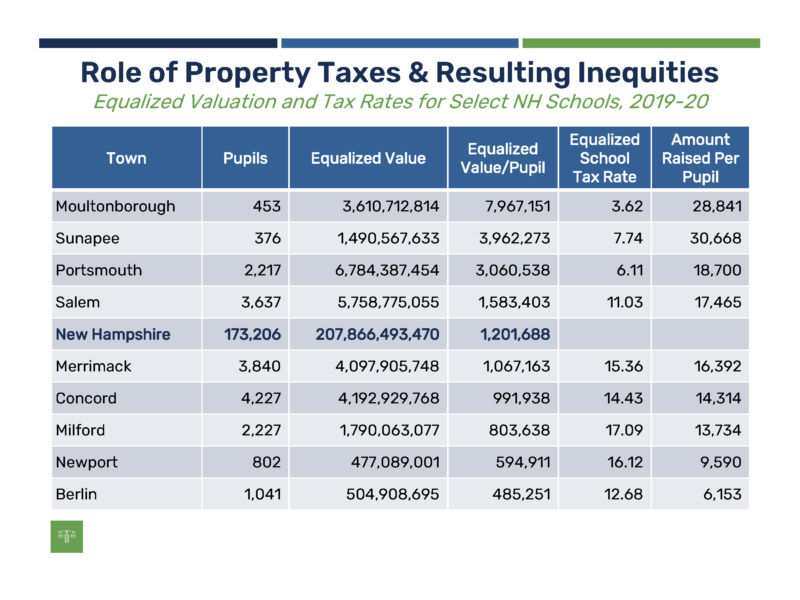

The inequities between the state’s wealthy and struggling communities are apparent, and stark: Students in property-rich communities are afforded many resources unavailable to students in property-poor towns. And, because of the nature of property taxes, taxpayers in many property-poor towns pay much higher tax rates to afford the same per-pupil spending as their counterparts in wealthy communities. For example: In 2019, the city of Berlin had less than $485,000 in equalized property value per pupil, compared to nearly $8 million per pupil in the town of Moultonborough, 50 miles and a world away (a more than 15-fold difference). That means that in order to raise the same dollar amount for each student, a household in Berlin would need to pay a property tax that is more than 15 times higher than a household in Moultonborough. Another group of districts sued the state in 2019, asserting that state adequacy aid would need to triple to meet the basic requirements set out in state law. In March, the state Supreme Court sent the “ConVal lawsuit” (so named for the Contoocook Valley school district, one of the districts that brought the suit) back to Superior Court.

The success of our communities, and our economy, is directly tied to how well our children do in our public schools — and not just some of our schools, and some of our children. All of our children, in all of our schools, in all of our communities.

New Hampshire is a state with an aging demographic and huge bubble of baby boomers headed toward retirement. Coupled with that, the majority of college-bound graduating high school seniors now leave the state for college — many then settling into jobs and communities elsewhere.

The urgency to make sure all of New Hampshire’s children can thrive in their local public schools is not just a matter of obligation to those children — it is a matter of shared prosperity for the future.

New Hampshire needs the children in every community to be nurtured and challenged by our schools to achieve their full potential. We need those kids to become the doctors and teachers and medical researchers and nurses and IT specialists and financial professionals and entrepreneurs and engineers who are going to keep our communities running tomorrow.

For more information, contact Michael Turmelle at 603-226-6641, ext. 147 or Zvpunry.Ghezryyr@aups.bet.