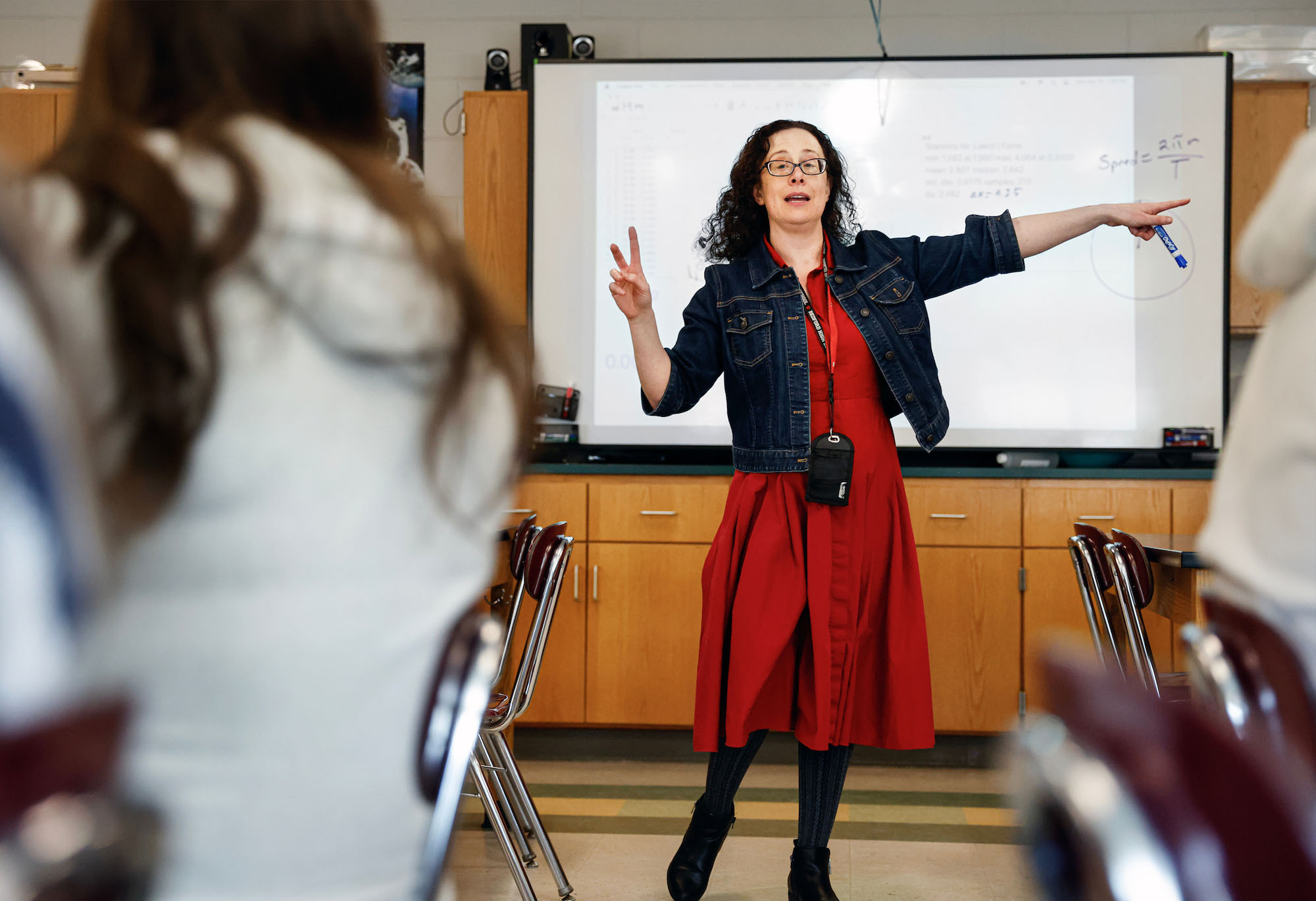

As a long-time physics teacher, Jennifer Baney knows science is serious, but she also knows that an effective way for students to grasp and apply serious and complicated concepts is to have fun.

“I’ve been a physics teacher now for 20 years and one of the things I’m passionate about is getting kids to see that physics isn’t dry and mathematic,” said Baney, who teaches at Bedford High School.

As the 2024 recipient of the Christa McAuliffe Sabbatical from the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation, Baney hopes to transform the way young people think about physics. She plans to help students develop the teamwork, critical thinking and problem solving skills needed to excel in science (and life) through sophisticated table-top escape room games.

Baney’s idea is to produce four digital games in which students will unravel a series of puzzles and challenges, each intricately designed to represent specific science concepts. She is designing games to be used in high school science classrooms, but they will be adaptable for a wide range of science topics and grade levels.

The sabbatical, created in 1986 in honor of the Concord High School teacher and astronaut, gives an exemplary New Hampshire teacher a year off with pay and a materials budget to bring a great educational idea to fruition.

Baney’s project was inspired by physical escape rooms, where participants solve clues to unlock the room and escape. In Baney’s tabletop games, students will apply scientific principles and test theories to achieve a goal with hands-on activities and role-playing – maybe finding treasure as pirates or fixing a problem in a spaceship as astronauts.

She is tackling two primary challenges in science education: keeping students motivated and helping them understand Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM).

For Baney, the best solution is having students collaborate in groups to solve science problems, not merely try to figure out solutions by learning a formula.

For instance, on paper, students can calculate where a projectile might land by learning a formula that includes its angle and velocity – not very motivating, Baney said.

“But if you’re a group of pirates and you need to get your cannon ball to land over there, so you can get a rope up there and get your hidden treasure, now you have a bunch of kids that are really invested in solving this problem,” she said. “They will roleplay and really get into it. They will make themselves a little paper pirate hats, and they will wear them for the rest of the day.”

Teachers around the state have agreed enthusiastically to help test games in their classrooms and provide feedback from their perspectives and from their students.

After supplementing her classroom observations and experience with research on student motivation, game theory and the benefits of game-based learning, Baney plans to develop two games. With teacher/student feedback, she plans to revise them and develop two more. All four will be available on a website for teachers to download, with comprehensive guides and easy-to-obtain materials that can be tailored for a class’s specific needs.

“I can imagine what’s going to work in my class. But I really want this to work for a huge amount of teachers,” she said. “So I want to see what works in everyone’s class, and then use that to hopefully have those second two games work out even better.”

Each game will be designed as a series of challenges linked by a narrative or storyline that guides students through the challenges, providing context and purpose.

Baney said studies show that following a narrative gives students real-world context for science lessons. The narrative helps show how theories were developed and why they need to understand them.

“What I really want them to take away from high school physics is problem solving – like they hit a wall and do not know what to do, so they have to back up, and on their own say, ‘Okay, what do I need to do get do to get through this?’ That’s so important for every aspect of life.”

Working to overcome a challenge, she said, is what research has shown keeps gamers and students engaged and motivated.

Baney’s science students have benefitted first-hand.

“Sometimes, my classroom kind of spills out into the hallways. We have model cars going down the hallways and we have a lot of sensors set up,” she said. “Science can be loud and sometimes science can be messy, but I think kids are really engaged when you teach this way.”

Sometimes, students build electric circuits, which also can be included in the escape room games.

“A lot of kids who it’s really hard to engage in other ways, when you give them wires and lights bulbs and a battery and ask them to build a circuit, those are the kids that will sit there for a sustained amount of time, and they’re gonna figure it out,” she said.

Baney hopes her innovative and customizable game challenges will help teachers inspire a love for physics, that more students become engaged with STEM and more enter STEM-related jobs in New Hampshire.

“I think too often, in trying to keep kids involved, we make things a little easier,” Baney said. “I’m going the exact opposite way. I think you need to ramp up the challenge and give them something that like tickles that part of their brain where they’re like, ‘How would I do that?’”

![Oluwakemi Olokunboyo of Dover received a McNabb scholarship to study nursing at Great Bay Community College [Photo by Cheryl Senter]](https://www.nhcf.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Scholarship-Hero-800x548.jpg)