The Boke of St. Albans, a 15th century sportsman’s handbook, decreed that only a nobleman could hunt with a falcon, but a mere yeoman might settle for a goshawk. These days it is the very wildness and willfulness of the goshawk that bestows a badge of courage on those who would train one.

By Thomas Ames, Jr.

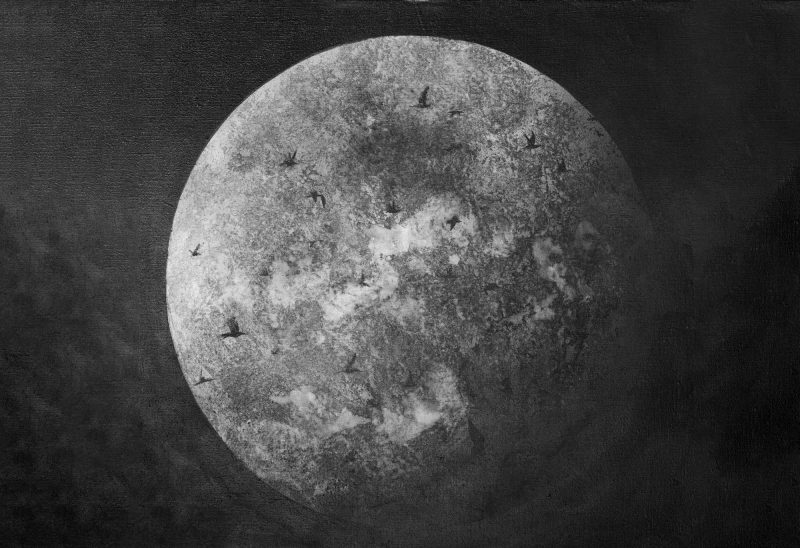

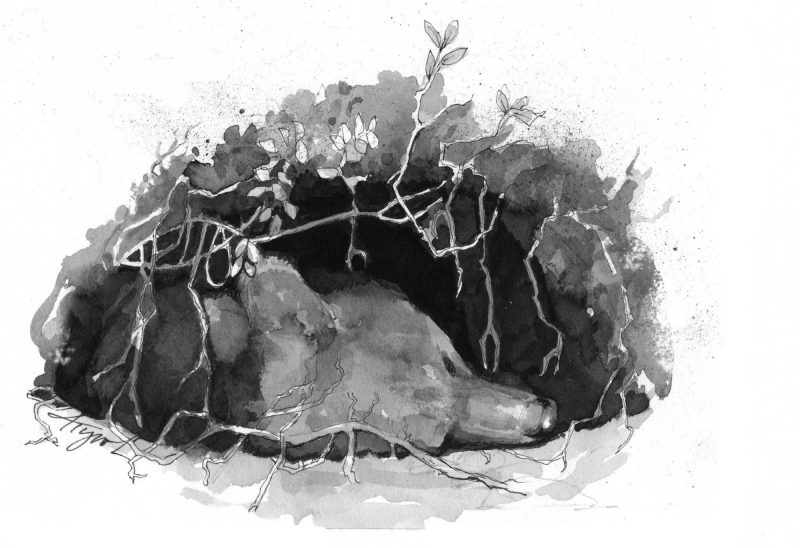

“In the talons there was death,” wrote T. H. White, who famously chronicled his naive attempt to “man” one of these “murderous” raptors in The Goshawk. “He would slay a rabbit in his grip by merely crushing its skull.” Goshawks are the largest of the accipiters, a genus that includes two exclusively North American species, the Cooper’s and the sharp-shinned hawks. Goshawks are identifiable by a white eyebrow stripe beneath a slate crown. In eastern North America, their range extends from Newfoundland south to Virginia’s Appalachian Mountains. They maintain distinct breeding and foraging territories within their range. Some adults and juveniles may be seen well outside of this area but, insisted David Brinker of Maryland’s Department of Natural Resources, who monitors goshawks and numerous other birds, this seasonal relocation is not migration.

Meghan Jensen, who studies the genetics and ecology of North American accipiters, explained that migration is unnecessary because many of the animals goshawks eat – crows, snowshoe hares, squirrels, grouse – don’t migrate either. As for the cold, said Jensen, “feathers are amazing insulators, much better than fur or hair.”

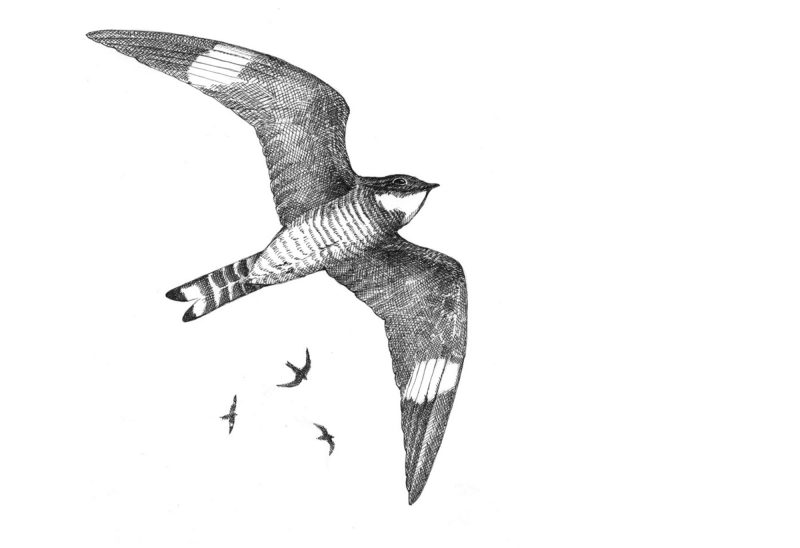

Jensen explained how goshawk wings are ideally suited to hunting in forests. Falcon wings are “long and sickle-shaped,” engineered for speed in the open sky. Eagles and red-tailed hawks have broader, deeper wings, adapted for soaring over open spaces. Goshawks are ambush predators of the woods; their shorter, rounded wings allow them to maneuver around and between trees and shrubs. Even with a wingspan averaging forty-six inches, a female goshawk can navigate a space no larger than her own girth.

The goshawk. Illustration by Adelaide Tyrol.

They’re relentless hunters. While other raptors will occasionally pursue their prey on the ground, goshawks and other accipiters make a habit of this behavior. “They will even crash through brush and potentially injure themselves in the process of running after a meal,” said Jensen. Collected specimens often reveal fractured pelvic girdles, or collarbones, that have healed after collisions with trees.

Goshawk breeding pairs typically return to the same nesting area for multiple years. In winter, however, they hunt independently. According to David Brinker, goshawks typically hunt away from the nesting area during the winter, to avoid depleting local prey populations, but will make occasional visits to the nesting area. Changes in the food supply may force them to change their plans. For example, a goshawk pair may depend heavily on snowshoe hares, which breed so prolifically that “they literally eat themselves out of house and home,” said Brinker. When the hare population crashes, the goshawks relocate.

Raising chicks is a co-operative venture. The male, or tiercel, maintains and defends the breeding territory, and is the first back to the nesting area. When the female arrives they build, or perhaps refurbish, a nest of small sticks that is, according to Brinker, “about the size of a bushel basket,” just under the canopy in a mature forest with an open understory. Should his mate fail to arrive, a male will court any young female who enters his territory. According to Jensen, it’s not clear whether the desirability of the male or the quality of the nesting area is what closes the deal.

Goshawks typically produce two to four eggs. Once she lays and incubates her eggs, the female rarely leaves the nest. She must protect her offspring from scavengers and from other birds of prey, and she’s notoriously effective at it, charging at any perceived threat, including humans. In patchy forests, her biggest threat may be a nighttime attack from a great horned owl. Mounting evidence, said Brinker, suggests that fishers account for a growing number of nest failures. “A fisher is capable of killing an adult female goshawk on the nest.”

The job of feeding the family falls mostly to the male. At roughly one third smaller than the female, he is a quicker and more nimble hunter than his mate. He is both monogamous and reliable. If you find a male at a nest with a female and chicks, Jensen assured me, you know he is the father.

No one is sure how well goshawks are faring in North America. Timber harvesting has prompted some monitoring of Western populations, especially in national forests. In the East, lamented Brinker, “there is no regional monitoring protocol in place … that really works.” What mapping data is available indicates that numbers have declined. In White’s England, where “nearly everything concerned with falconry was illegal” except falconry itself, human activity had eradicated native goshawk populations. Ironically, it is the falconers, holdovers from a bygone age, whose release of captive goshawks into the wild has restored them.

This week’s Outside Story feature was written by Thomas Ames Jr., an author and photographer of numerous books and articles on aquatic entomology for fly fishers, including Fishbugs and Caddisflies, A guide to Eastern Species for Anglers and Other Naturalists. In 2009 he traded in his darkroom for a classroom full of fifth graders in Canaan, New Hampshire. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation. Illustration by Adelaide Tyrol.