By Joe Rankin

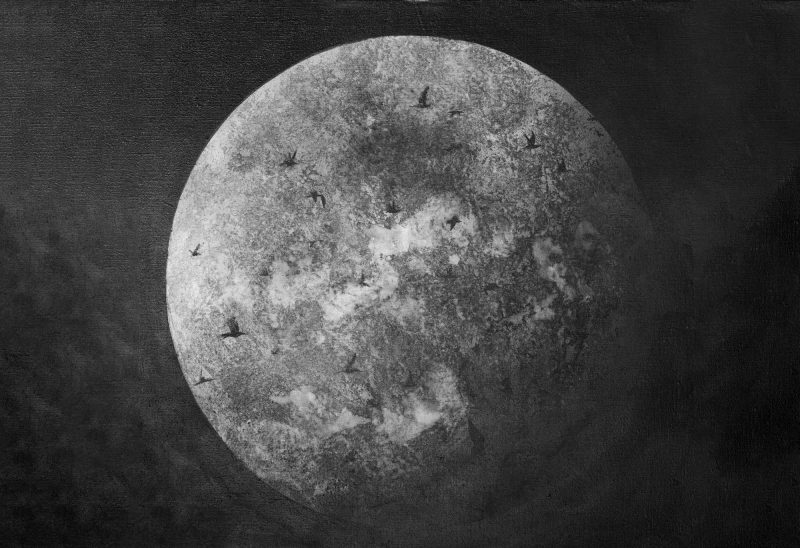

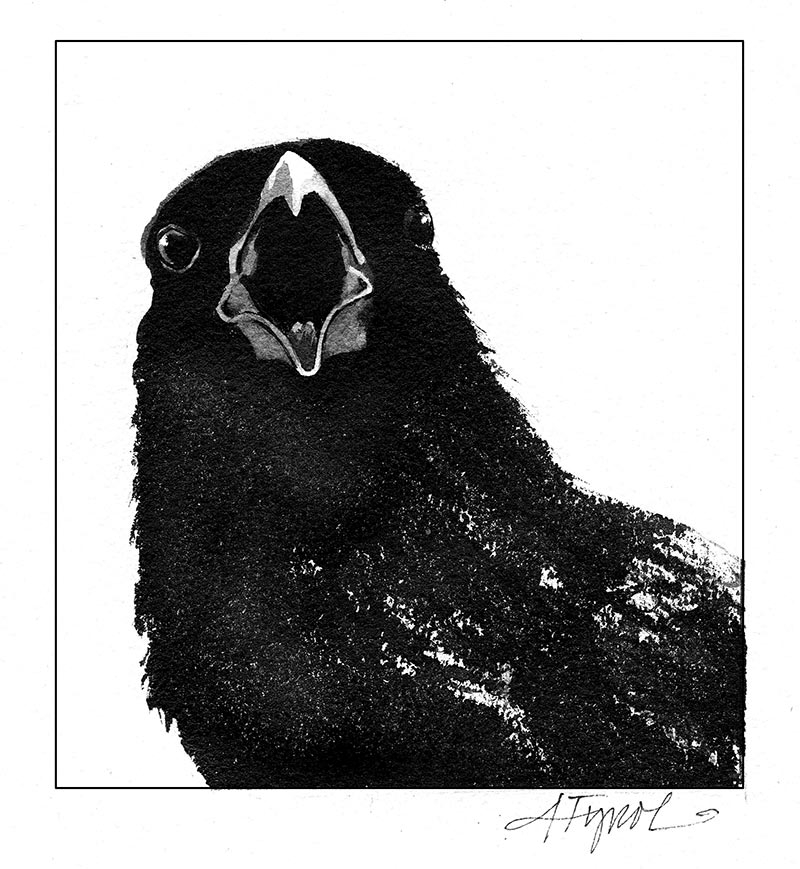

“Caw! Caw!” Every spring we hear it. And my wife says, “that’s My Crow.” It’s apparently the bird’s name. She capitalizes it in her tone. I think she hasn’t bestowed a more formal name because she doesn’t know whether it’s a male or female.

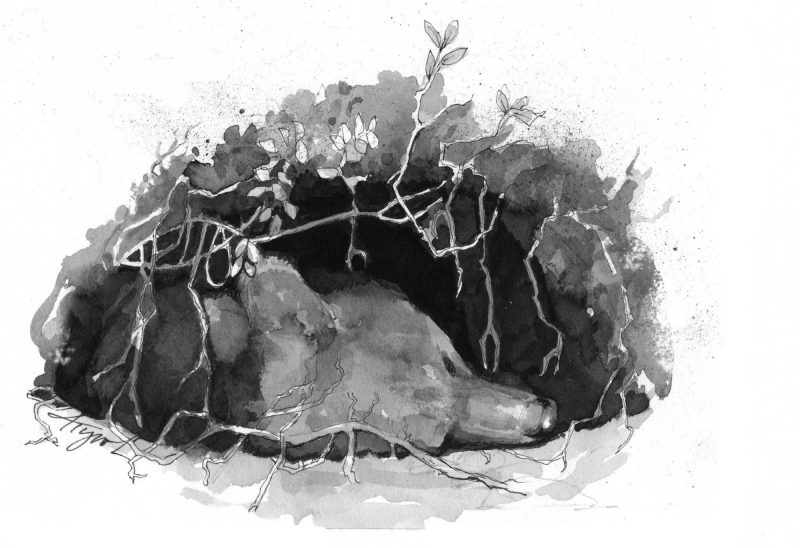

My Crow is likely part of an extended family of crows that lives in our area. We think they nest in the tall pines on our south neighbor’s woodlot, but they forage over our woods and fields as well.

“How do you know it’s your crow?” I ask. “I can tell by the sound of its voice,” she says. “It’s different. Raspier. It makes a sort of throaty chuckle the other crows don’t make.”

This may sound improbable, but research has shown that crow voices vary by individual. “There’s enough information in [the sound] that, in theory, the crows could tell each other apart,” said Kevin McGowan of the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, who has studied crows and their calls for years. “It’s like human voices. Even though some may be similar, you can usually distinguish among them. I know that I recognized my dad clearing his throat from two aisles over in the grocery store.”

Crows – there are perhaps as many as 40 species worldwide, including the American crow, Corvus brachyrhynchos – are highly intelligent. Some not only use tools, but create them out of straw, wood, or wire to access food. They also play. Recent research has shown that they employ analogical reasoning and recognize faces of individual people. They have a complex social structure and their nuanced communications reflect that.

Illustration by Adelaide Tyrol.

A “caw” can mean different things, depending on how it’s used, the energy put into it, the timbre, the number and speed of repetitions. “Crows may be more complex communicators than other birds,” said McGowan.

McGowan has also studied the Florida scrub jay, a crow relative. He likens scrub jay to a romance language like Spanish, where pronunciation is pretty consistent. Crow is more like Mandarin or Vietnamese, very complex tonal languages where the same “word” can mean different things depending on tone and how it’s used.

McGowan considers himself fluent in scrub jay, but only conversant in crow. “I know when they’re talking about predators or their neighbors or they’re talking within the family. I know when they’re saying, ‘here comes somebody with a dog, we might have to watch out for it’ or ‘there’s a fox over here, let’s go yell at it,’ those kinds of things.”

After 27 years of studying crows, they still manage to surprise him, giving a call that he thinks he knows and then doing something unexpected.

There’s a lot in crow-speak that has to do with the timing of the notes, the space between them, and how quickly they are uttered, he said. In that way it may be as useful to compare it to human-created music as language. Think pianissimo versus fortissimo. Same notes, different delivery.

“There’s a call they give that says ‘heads up everybody, there’s a hawk.’ But they can also indicate ‘it’s getting closer, now we better hide.’ It’s the same word, but they speed up, ‘cawcawcaw.’ Finally they change into a very different vocalization, which means ‘hide,’” McGowan said.

The crow’s complex intra-species communication system reflects its complex social life. Crows generally live in family groups, with young adult birds sticking around to help their parents care for this year’s fledglings. In their home territory they’re always on the alert for threats, and quick to share information with the rest of the group. They’re quick to invite crows from neighboring territories to help harass an owl or a hawk. “They have a great neighborhood watch system,” said McGowan.

Crows from many families and neighborhoods gather in huge flocks, sometimes numbering in the thousands, on foraging grounds or at communal roosts during winter. It’s the crow equivalent of humans going to the mall or the beach at Cancun and hanging out with strangers.

McGowan said there’s a lot yet to learn about crow communication. New technology, ranging from GPS to directional microphones and acoustic computer algorithms, has the potential to vastly expand our understanding of what their lives are like, he said.

Despite their intelligence – recognized since ancient times – many people view these birds as a nuisance. Consider the word for a group of crows – a “murder.” McGowan really dislikes that. “It plays into people’s negative attitudes toward crows,” he said. “I’ve suggested changing it to a ‘bouquet’ of crows, but I’m not getting a whole lot of traction on that.”

This week’s Outside Story feature was written by Joe Rankin, who writes on forestry, nature and sustainability from his home in central Maine. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation. Illustration by Adelaide Tyrol.